The Formative Years: How ITL Inspired Cavalier’s Competitive Way

Published Apr 30, 2021 | Posted in Cavalier, Industry, News, Technology, Uncategorised

By Nick Krewen

Business Writer

Without the pioneering efforts of Windsor-based International Tools Limited or as many in the plastics industry would know it ITL, there would have been no emergency triangles, no safety reflectors, no childproof caps…and perhaps no Cavalier Tool.

“We’ve taken quite a few pages out of the ITL handbook,” admits Brian Bendig, President and Owner of Cavalier Tool & Manufacturing.

“They were innovators in so many areas, but our connection goes deeper than that, as Cavalier was founded as a direct offshoot of ITL.”

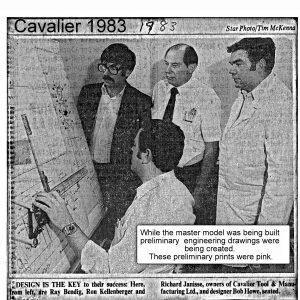

In fact, in 1975, Cavalier Tool’s three founders – and former ITL employees – CNC leader Ray Bendig, Toolmaking Leader Rick Janisse and former Kelly Tool owner and operator Ron Kellenberger opened their rented facility at 4970 E.C. Row in Windsor near the Ontario/Michigan border.

But it was ITL that taught them the ropes as craftsmen long before they ventured out on their own.

“Many companies, including Cavalier, can trace their roots back to ITL,” says Mike Hicks, a former ITL employee who is currently Director of Sales at Die Mold Services Canada.

“I estimate that 25 to 35 shops came out of the ITL fold, but it could be more.”

ITL: The Origin of Windsor’s Pioneer Moldmakers

Founded by Peter Hedgewick in 1945, the company basically put Windsor on the plastics and moldmaking map.

Hedgewick, a former $0.62-an-hour Chrysler production line worker who apprenticed as a toolmaker at Standard Machine for only $0.15-an-hour, forged the connection with Windsor Tool-and-Die Limited and later Windsor Tool and Mould Limited that set him on his visionary career path.

In 1945, he sank his savings to found International Tool LTD and, in essence, launched the Canadian plastic moldmaking industry.

Recruiting skilled immigrants from Europe at the end of World War II, Hedgewick enlisted them to train hundreds of moldmakers at ITL.

“They brought a wealth of knowledge to ITL with their labour pool,” says Mike Hicks, adding that the hirings later backfired on him.

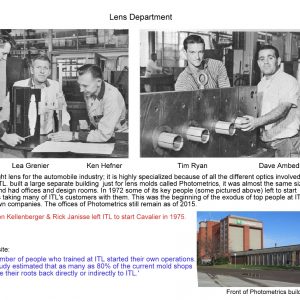

“Hedgewick empowered so many people in their positions that ITL created its own competition,” Hicks notes. “One of the biggest shops was Hallmark Tools – they’re the people who did the lens work, the taillights – and that was one of the biggest ties to ITL, because of their lighting technology. Hallmark took some of the key people that were involved.

“Also, Active Mold started their own lighting division.”

Along the way, ITL made some innovative discoveries that are still with us today.

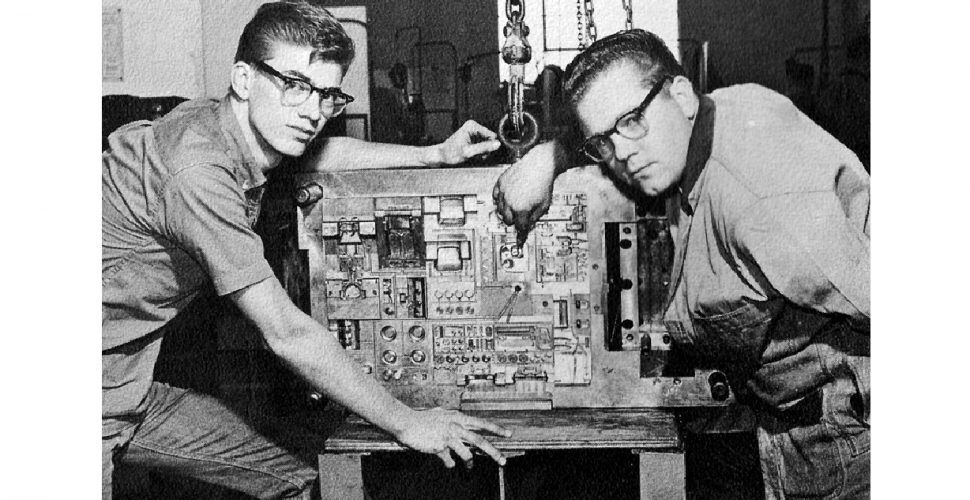

In 1960, industry trade magazine Canadian Plastics reported that ITL provided the tooling for the first major use of HDPE in an automotive application supplied to the Ford Motor Company. This project involved the development of front seat side shields made of polyethylene for the auto manufacturer’s North American ‘60s model vehicles.

The ITL Innovations

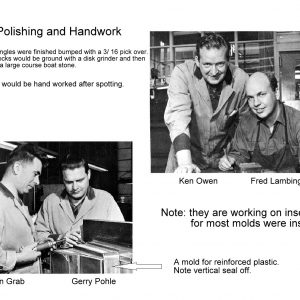

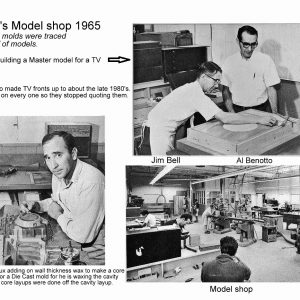

That wasn’t the only pioneering development that ITL contributed to the world: aside from building master models for television, taillight lens and chrome grills for the auto industry, they also supplied tooling for numerous plastic parts for autos as by 1970, plastic had begun to replace die cast and stamped steel on many auto parts due to its lighter weight, lower price point and lower tooling cost.

ITL also invented emergency triangles, often posted behind trucks to signal they’re parked on the side of the road. They also created roadway embedded reflectors that ensure vehicle stick to their side of the road at night.

But ITL’s biggest impact was the palm-and-turn technology of the child safety prescription cap, created at the request of Windsor’s Dr. Henri Breault, in response to his quest to prevent accidental child poisoning. Breault asked Hedgewick to invent and manufacture the child-resistant cap.

Available in 1967, the introduction of the cap reduced child poisonings in the Windsor area by 91%. It was so successful that by

1974, the Ontario government made child-resistant containers mandatory, and the rest of the world followed shortly thereafter.

At the pinnacle of its ‘70s success, ITL had sales of $21.5 million, a company valuation of $3 million and an employee count of 700. It was one of the largest moldmaking operations in North America– and its close proximity to Detroit, the capital of auto manufacturing, secured its importance to the industry.

But ITL was not built to last: obsolete equipment and local competition eventually forced the company into bankruptcy in 1987.

“After I was at Cavalier at the new building in 1980, it was all nice and white and shiny and had air conditioning,” Ed Bendig, who joined Cavalier as a veteran licensed mold maker and the company’s first employee in 1976 recalls. “We were in there six months and I had to go to ITL and visit for some reason. It almost knocked me over – there’s no air conditioning, the floor is soaked with oil and grease, the ceilings were really low and there was dirt all over the place. It actually shocked and appalled me, because I didn’t remember it like that, but that’s the way it was. And you just got used to it.

“I understand that that’s how they slowly lost customers. They had really old machines and they never really updated.

“They did in the ‘60s, but things changed in the ‘80s. They just never updated. They were running the old machines.”

Cavalier: The Early Years

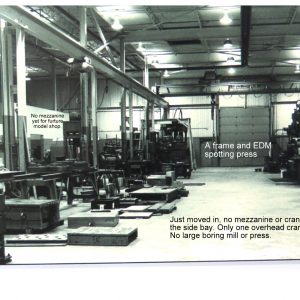

The machines at Cavalier were also used when the company first opened its doors – on the very day, no less, the current president Brian Bendig was born. Each of the three partners invested $7500 (the equivalent of $36,925 today) – to rent half a building at 4970 E.C. Row in Windsor that covered 4000 sq. ft of shop area.

Their initial inventory included a small two-ton crane, a spotting press, a small boring mill, two surface grinders and two Bridgeports, amongst other things.

“That spotting press had a good run,” recalls Ed Bendig,

“It lasted from 1975 to 2014.”

Cavalier’s very first job had nothing to do with the auto industry: they provided the mold for four blades for a Heineken beer display windmill.

Slowly, more equipment was added and Cavalier expanded their mold expertise to include wheel covers, refrigerator door handles, front plastic for dishwashers, Rockola jukeboxes (Ed Bendig estimates he made about seven of them) and smaller automotive parts.

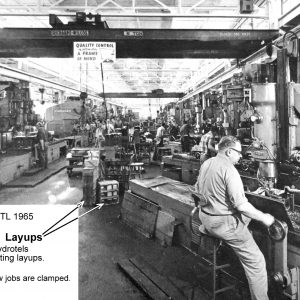

By late 1976, Cavalier had added more equipment to its floor – including an EDM, a Keller, a Deckel, a Hydrotel and a 5-ton crane – that helped beef up the quality of the molds it produced to a competitive standard.

In 1980, buoyed by good business, Cavalier expanded and built a plant for $400,000, located at 3450 Wheelton Dr., but fell into a negative cash flow in 1981 and reached the point where the owners had to stop taking a paycheque in order to make payroll.

Hiring a business consultant, they obtained a loan from the Federal Business Development Bank that could be described as a “lifesaver” and turned the shop around to the point where they were awarded the FBDB’s “Business Management Award” in 1983 – the first Windsor winners to do so.

In 1985, Cavalier was the first shop to adopt CNC (Computer Numerical Control) technology, retrofitting a Hydrotel duplicator and using a programmable Heathkit H-8 computer to control it.

By the turn of this century, personnel changes were afoot at Cavalier, as an illness reduced Ray Bendig’s employment to part-time hours. Ron Kellenberger was diagnosed with cancer. Rick Janisse hired a new CEO to run the company.

There were also bigger problems: molding companies began relocating to China and suddenly work dried up. In 2008, Cavalier’s current president and owner Brian Bendig, took over. The new “head coach” strategically aligned his team and empowered them under his guidance, focused on working together, calling the right plays at the right time. The results speak for themselves.

New Head Coach makes right plays at right time

“Brian took over a struggling company,” remembers Ed Bendig. He made the right moves at the right times.” As head coach, he made it a priority to get rid of the older, obsolete equipment, slowly replacing it with more modern technology bought at a discount price and at auctions from shops that were going out of business.

“Brian would use these machines for four years at Cavalier and then sell them for close to what he paid for them,” Ed Bendig recalls.

Brian Bendig used these “bridge machines” to catapult Cavalier to the forefront of technology, and continued to invest in equipment, technology and people while “decluttering” the floor.

The constantly upgraded and updated automation allowed for more accurate designs, quicker delivery and reduced costs, as top-of-the-line machines held tighter tolerances that help extend tool life and resulted in high-quality molds.

Introducing The Spirit of Competitive Collaboration

He also injected the spirit of collaboration between shops and manufacturers and encouraged people to share information in order to improve equipment operation.

“Brian would bring people together and look at how you could do things better,” recalls Ed Bendig. “He did a lot of that with graphics, saying, ‘this is what your software should be doing, so we want to work with your engineers. We will help you show the way that we want you to do this. This is what we need to be automated.’

“It made designing molds a lot better. Brian is great at bringing people and businesses together to help each other, which resulted in helping them be more competitive.”

And then there’s the concept of the Cavalier Army – the 200-strong workforce that contributes as a team and shares in the victory through celebrations, prizes and group get-togethers. It’s management’s way of showing appreciation for the teams hard work.

With Cavalier’s tri-pillared emphasis on People, Process and Equipment, led by Brian Bendig’s unparalleled vision, the award-winning company achieved $52 million in annual global sales in 2020 and has expanded its reach internationally, with divisions in the U.S. and India, and market inroads into Latin America.

Mark Stephen, Editor of Canadian Plastics, says, “Brian has a very good reputation and Cavalier’s one of the biggest shops around.

“They’re known for being one of the more innovative companies as far as helping their customers come up with applications that couldn’t have been made out of plastic beforehand.”

The Cavalier Mission and Mandate

They’ve come a long way from the “pencil-and-paper math days” of their humble beginnings, and today the name “Cavalier Tool and Manufacturing Ltd.” represents trust, innovation, world-class product and speedy turnarounds.

“Our earliest roots may have begun with ITL, but we’ve worked hard to establish our own global presence and reputation with a team that looks to excel in everything we do,” says Brian Bendig.

“At the end of the day, we’re always pushing forward towards new frontiers for our clients in diverse areas in the automotive, commercial, agricultural, recreational and heavy truck industries.

“We are focused on growing and improving our efforts and offerings through reinvestment and always aiming to be the best.

“It’s the Cavalier Way.”